Anastasiia Pestinova

El atardecer era un festín – el amanecer se consumía

Ardiendo en la cara de un enemigo ebrio

Desde la tierra natal hasta el séptimo cielo

Furiosa y ruidosamente llegó el sonido: “¡Victoria!”

La puesta de sol estaba de fiesta – el amanecer estaba muriendo

El dolor retrocedió, gotas escarlata

Cayeron de la cruz, y los labios muertos

Orgullosa y obstinadamente susurraron: “¡Victoria!”

Deseo levantarme de cuerpo entero – pero no hay piernas

Apretar mi palma en un puño – pero no hay nada que apretar

No hay más palabras, no hay más “nosotros”

Sólo queda una cosa en el mundo – la Victoria.

Nuestra victoria.

Nuestra victoria.

- El músico, poeta y artista soviético y ruso Yegor Letov es uno de los representantes del underground siberiano y padre de la escena industrial rusa. A lo largo de su vida, creó numerosos proyectos artísticos, entre ellos “Grazhdanskaya Oborona” (Defensa Civil), “Instruktsiya po Vyzhivaniyu” (Instrucciones para la supervivencia), “Comunismo” y otros. Es un vivo ejemplo de la disidencia soviética, ya que fue sometido en repetidas ocasiones a la persecución política y a la represión, y también se vio obligado a pasar por un tratamiento obligatorio en un hospital psiquiátrico, durante el cual no dejó de hacer poesía para no derrumbarse y no perder el resto de la personalidad.

Los textos de Letov están llenos de angustia existencial, ironía cáustica, humor negro y metáforas que socavan el lenguaje -una de las más famosas es “la eternidad huele a aceite”-, una afirmación que penetra en la raíz de la agenda político-económica y que fue expresada casi tres décadas antes del pensamiento de R. Nagerestani.

En el texto de la canción “Victory”, del álbum “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, los labios muertos susurran obstinadamente la palabra “victoria”, a pesar de que la personalidad, junto con la vida y las partes del cuerpo, desaparecen / se destruyen en sus rayos marchitos y aniquiladores. Vencer a pesar de la vida, a pesar de la pérdida de uno mismo, ser crucificado en la cruz de la victoria, ¿es éste el destino que queremos?

Letov erosiona los límites conceptuales habituales de lo que se entiende por guerra. En lugar de un pathos heroico, se nos ofrece una visión trágica de la relación entre el individuo y el sistema, el “heroísmo de la derrota”. En el espíritu de J. Bataille, niega el carácter utilitario de la guerra y afirma que la guerra es un “derroche improductivo”. Deconstruyendo el mito de la Segunda Guerra Mundial como base de la identidad soviética, intenta convertirlo en un mito metafísico, en un mito sobre la guerra como trauma colectivo, intentando así reactivar la memoria histórica. Quizá una identidad basada en la tragedia y el reconocimiento de la experiencia traumática tenga más futuro que una basada en el heroísmo.

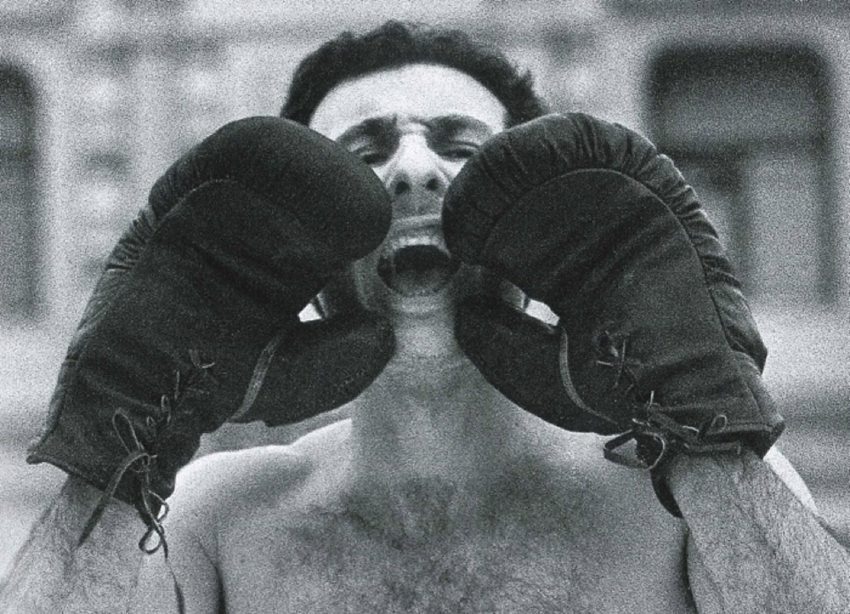

- Nacido en Alma-Ata en 1957, Alexander Brener es un artista de origen judío y representante del Accionismo Moscovita, un movimiento de artistas caracterizado por la transgresión, el radicalismo y la provocación. Brener solía actuar como una especie de santón, organizando escándalos sobre diversos temas sociales y políticos. Sus acciones se caracterizan por lo que puede describirse como la poética del fracaso, ya que no se vieron coronadas por el éxito, sino que fracasaron una y otra vez, deliberadamente o no. Según el galerista y gestor de arte M. Gelman: “Todas sus actuaciones estaban asociadas a todo tipo de complicaciones y a menudo causaban muchos problemas”.

Entre sus acciones destaca el “Primer Guante”, realizado en febrero de 1995. Estaba dedicado a la Primera Guerra de Chechenia que lanzó Rusia en diciembre de 1994 y que duró dos años. Brener salió en calzoncillos y guantes de boxeo a la Plaza Roja al grito de “Yeltsin, sal” para pedir cuentas al presidente por la actuación de las tropas rusas. Nadie acudió a sus llamadas, salvo la policía, que lo detuvo rápidamente.

La positividad de la influencia del accionismo es controvertida y es criticada tanto por las autoridades como por los artistas por su efecto de choque y por destacar la figura del performer, que no cambia la situación política, no ofrece ninguna solución concreta, sino que sólo sabotea al público. Sin embargo, incluso la mera formulación de la cuestión en forma de cuerpo vivo opuesto al orden simbólico que establece los límites de lo que se puede hacer y decir, y de lo que no, representa una visión crítica de la sociedad sobre sí misma y por ello tiene un valor. Según J. Butler, filósofa estadounidense que propuso su teoría de la performatividad, los cuerpos como tales, en su silenciosa presencia espacial, están llenos de sentido y son portadores de significado político. Mientras tanto, el régimen de un Estado está determinado por dónde y bajo qué circunstancias se permite la presencia de los cuerpos, y dónde y bajo cuáles – no.

- La animación soviética es un verdadero almacén de arte, en el que se puede encontrar una gran variedad de tramas: fantástica, surrealista, sátira social, utopías y distopías. Por supuesto, el tema militar no podía escapar a la atención de los animadores. El dibujo animado de 1977 con el pesado título de “Polígono”, filmado por Anatoly Petrov y basado en una historia fantástica escrita por Sever Gansovsky, es una cinta de diez minutos creada con una tecnología fotográfica especial.

En el centro de la trama, vemos un tanque que tiene la capacidad específica de leer los pensamientos de la gente. Para activar el modo de defensa, el tanque necesita captar el impulso de odio, el deseo de destruir el tanque que proviene de un humano. A la inversa, para activar el modo de ataque, el tanque necesita captar el impulso del miedo. “El enemigo controla las acciones del tanque en contra de su voluntad”, dice el científico, y es una afirmación vívida que demuestra la interconexión de los oponentes. En la naturaleza de cualquier conflicto se esconde una simbiosis de fuerzas opuestas, su alimentación mutua, la codependencia. Respectivamente, el conflicto sólo puede resolverse con la conciencia de esta profunda conexión. El Tanque -materia inorgánica y muerta, la encarnación de la muerte- está dotado de cualidades no sólo humanas, sino sobrehumanas, telepáticas, asemejándose así a algo parecido al Océano de Solaris.

Ni los soldados ni el científico-creador pueden llevarse bien con este tanque, ya que todos tienen algunos motivos ocultos y tensiones no resueltas en su interior. Sólo una tribu de salvajes y sus hijos -el dibujo animado termina con un plano que representa a niños aborígenes jugando sobre un tanque- encuentran la armonía con esta máquina, que es en su naturaleza una prueba de fuego, una imagen especular del entorno en el que aparece. No nos fijemos demasiado en las posibles referencias coloniales de un noble salvaje, a las que recurre el autor de la trama. Lo más importante es que si el entorno está impregnado de conflicto, la máquina lo intensifica y lo lleva a la descarga, a la aniquilación, y si el entorno está en calma, entonces la máquina no actúa. Al igual que en muchas otras obras de ciencia ficción (recordemos, por ejemplo, la película “Aniquilación” de Alex Garland), vemos un escenario en el que la humanidad genera una entidad que resulta ser una lección para esta humanidad, demostrando sus debilidades y límites.

Пиpовал закат — выгоpал pассвет

Полыхал в лицо пьяному вpагу

От pодной земли до седьмых небес

Яpостно и звонко звучало: «Победа!»

Пиpовал закат — умиpал pассвет

Отступала боль, алая капель

Падала с кpеста, а мёpтвые уста

Гоpдо и упpямо шептали: «Победа!»

Стать бы во весь pост — да нету больше ног

Сжать ладонь в кулак — да нечего сжимать

Hету больше слов, нету больше нас

Лишь одно осталось на свете — Победа.

Hаша Победа.

Наша Победа.

- Советский/российский музыкант, поэт и художник Егор Летов является одним из представителей сибирского андерграунда и отцом русской индустриальной сцены. На протяжении своей жизни он создает множество арт-проектов среди которых «Гражданская оборона», «Инструкция по выживанию», «Коммунизм» и другие. Выступает ярким примером советского диссидентства, поскольку не раз повергался политическим гонениям и репрессиям, а также был вынужден проходить принудительное лечение в психиатрической больнице, в течение которого не переставал писать стихи, чтобы не сломаться и не утратить остатки личности.

Тексты Летова полны экзистенциального надрыва, едкой иронии, черного юмора и метафор, подрывающих язык – чего только стоит знаменитое «вечность пахнет нефтью» – фраза зрящая в корень политико-экономической повестки и высказанная за почти три десятилетия до размышлений Р. Нагерестани.

В приведенном тексте песни «Победа» из альбома «Невыносимая легкость бытия» мертвые уста упрямо шепчут слово «победа», несмотря на то что личность вместе с жизнью и частями тела исчезают/уничтожаются в ее испепеляющих ничтожащих лучах. Победить вопреки жизни, вопреки утрате самого себя, быть распятым на кресте победы – этой ли участи мы желаем?

Летов размывает привычные границы того, что понимается под войной. Вместо героического пафоса, нам предлагается трагический взгляд на отношения между индивидом и системой или «героизм поражения». В духе Ж.Батая он отрицает утилитарный характер войны и утверждает войну как «непроизводительную трату». Деконструируя миф о Второй мировой как базовый для советской идентичности, он превращает его в миф метафизический, миф о войне как коллективной травме, таким образом осуществляя попытку перепрошить историческую память. Возможно, что идентичность в основу которой будет положен трагизм и признание травматического опыта имеет больше будущего, чем та, в основании которой лежит героика.

- Александр Бренер родился в Алма-Ате в 1957 году, является художником еврейского происхождения и представителем московского акционизма – движения перформеров, отличающегося трансгрессивностью, радикальностью и провокационностью. Бренер выступает в роли своеобразного юродивого, устраивая скандалы на самые различные социальные и политические темы. Его акции характеризуются тем, что можно обозначить как поэтика неудачи, поскольку не увенчивались успехом, но каждый раз проваливались умышленно или нет. По словам галериста М.Гельмана: «Все его перформансы были связаны со всяческими осложнениями и часто вызывали кучу проблем».

Среди его акций выделяется «Первая перчатка», совершенная в феврале 1995 года и посвященная Первой чеченской войне, начатой Россией в декабре 1994 и продолжавшейся в течение двух лет. Бренер вышел в боксерских трусах и перчатках на Красную площадь с криками «Ельцин, выходи», чтобы призвать президента к ответу за действия российских войск. На его призывы не вышел никто кроме полиции, которая его быстро арестовала.

Позитивность влияния акционизма является спорной и критикуется как властью, так и художниками за эпатирование и выпячивание фигуры перформера, которые не меняют политическую ситуацию, не предлагают никаких конкретных решений, но только саботируют публику. Тем не менее сама постановка вопроса в виде живого тела противопоставляемого символическому порядку, устанавливающего границы того, что можно делать и говорить, а что нельзя, является как бы критическим взглядом общества на самое себя и представляет ценность. Так согласно Д.Батлер, которая предложила свою теорию перформативности, тела как таковые, в их молчаливом пространственном присутствии имеют значение и несут политический смысл, а режим того или иного государства определяется тем, где и при каких обстоятельствах тела присутствовать могут, а где и при каких – нет.

- Советская анимация – это настоящая кладезь искусства, в которой можно найти самые разнообразные сюжеты: фантастические, сюрреалистические, социальную сатиру, утопии и антиутопии. Конечно же и военная тема не могла ускользнуть от зорких глаз аниматоров. Мультфильм 1977 года с тяжеловесным названием «Полигон», снятый Анатолием Петровым по фантастическому рассказу Севера Гансовского представляет собой десяти минутную ленту, созданную по особой технологии фотографики.

В центре сюжета находится танк, обладающий способностью читать мысли людей. Чтобы активировать режим защиты, танку необходимо уловить импульс ненависти, желание уничтожить танк, идущее от человека. И наоборот, чтобы активировать режим атаки, танку необходимо уловить импульс страха. «Противник против своей воли руководит действиями танка» – яркое утверждение демонстрирующее взаимосвязанность противников. В природе любого конфликта заложен скрытый симбиоз противостоящих сил, их как бы подкармливание друг друга, созависимость, соответственно и конфликт может быть разрешен только с осознанием этой глубинной связки. Танк – неорганическая, мертвая материя, воплощение смерти, оказывается наделен не просто человеческими, но сверхчеловеческими, телепатическими качествами, напоминая тем самым что то вроде Океана из Соляриса.

Ни у военных, ни у ученого-создателя не получается ужиться с танком, поскольку все они имеют задние мысли. Только племя дикарей и дети – мультфильм завершается кадром детей аборигенов, играющих на танке – находят гармонию с этой машиной, которая является лакмусовой бумажкой, зеркальным отражением той среды, в которой пребывает. Не будем сильно концентрироваться на около-колониальном образе благородного дикаря, к которому прибегает автор сюжета. Главным является то, что если среда пронизана конфликтом, машина этот конфликт эскалирует и доводит до разрядки, до аннигиляции, а если среда спокойна, то машина не действует. Так же как во многих других научно-фантастических произведениях (вспомним, фильм «Аннигиляция» Алекса Гарленда) мы видим сценарий того, как человечество порождает сущность, которая оказывается этому человечеству уроком, демонстрирует его слабые места и границы.

The sunset was feasting – the dawn was burning out

Blazing in the face of a drunken enemy

From native land to the seventh heaven

Furiously and loudly came the sound: “Victory!”

The sunset was feasting – the dawn was dying

The pain receded, scarlet drops

Fell from the cross, and dead lips

Proudly and stubbornly whispered: “Victory!”

I wish to stand up full-length – but there are no legs

Squeeze my palm into a fist – but there is nothing to squeeze

There are no more words, there are no more «us»

There is only one thing left in the world – Victory.

Our Victory.

Our Victory.

- Soviet and Russian musician, poet and artist Yegor Letov is one of representatives of the Siberian underground and father of the russian industrial scene. Throughout his life, he created lots of art projects, among which “Grazhdanskaya Oborona» (Civil Defence), “Instruktsiya po Vyzhivaniyu” (Instructions for Survival), “Communism” and others. He is a vivid example of Soviet dissidence, since he was repeatedly undergone to political persecution and repression, and was also forced to go through compulsory treatment in a psychiatric hospital, during which he did not stop making poetry in order not to break down and not to lose the remnants of personality.

Letov’s texts are full of existential anguish, caustic irony, black humor and metaphors that undermine the language – one of the most famous is “eternity smells like oil” – an affirmation that permeates into the root of the political-economic agenda and was expressed almost three decades before R. Nagerestani’s thoughts.

In the text of the song “Victory” from the album “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” dead lips stubbornly whisper the word “victory”, despite the fact that the personality, along with life and body parts, disappear / are destroyed in its withering, annihilating rays. To win in spite of life, in spite of the loss of oneself, to be crucified on the cross of victory – is this the fate we want?

Letov erodes the usual conceptual boundaries of what is meant by war. Instead of heroic pathos, we are offered a tragic view on the relationship between the individual and the system, the “heroism of defeat”. In the spirit of J. Bataille, he denies the utilitarian nature of the war and affirms the war as “unproductive waste.” Deconstructing the myth of the Second World War as a basic for the Soviet identity, he makes an attempt to turn it into a metaphysical myth, into a myth about the war as a collective trauma, thus making an attempt to reflash historical memory. Maybe an identity based on tragedy and recognition of traumatic experience has more future than one based on heroism.

- Born in Alma-Ata in 1957, Alexander Brener is an artist of Jewish origin and a representative of Moscow Actionism, a movement of performers characterized by transgressiveness, radicalism and provocation. Brener used to act as a kind of holy fool, arranging scandals on a variety of social and political topics. His actions are characterized by what can be described as the poetics of failure, since they were not crowned with success, but each time failed deliberately or not. According to gallery owner and art-manager M. Gelman: “All his performances were associated with all sorts of complications and often caused a lot of problems.”

Among his actions stands out the “First Glove”, conducted in February of 1995. It was dedicated to the First Chechen War that was launched by Russia in December 1994 and lasted for two years. Brener went out in boxing shorts and gloves to Red square shouting “Yeltsin, come out” to call the president to account for the actions of the Russian troops. No one came out to his calls except the police, who quickly arrested him.

The positivity of the influence of actionism is controversial and is criticized by both the authorities and artists for shocking effect and for sticking out the figure of the performer, who does not change the political situation, does not offer any specific solutions, but only sabotage the public. Nevertheless, even the mere formulation of the question in the form of a living body opposed to the symbolic order that sets the boundaries of what can be done and said, and what – cannot – represents a critical view of society on itself and for this reason has a value. According to J. Butler, American philosopher that proposed her theory of performativity, bodies as such, in their silent spatial presence, are full of sense and do carry political meaning. Meanwhile the regime of a state is determined by where and under what circumstances bodies are permitted to be present, and where and under which – are not.

- Soviet animation is a real storehouse of art, in which you can find a wide variety of plots: fantastic, surreal, social satire, utopias and dystopias. Of course, the military theme could not escape the animators’ attention. The cartoon of 1977 with heavy title «Polygon» (Proving ground), filmed by Anatoly Petrov and based on a fantastic story written by Sever Gansovsky, is a ten-minute tape created using a special photographic technology.

In the center of the plot, we see a tank that has specific ability to read people’s thoughts. In order to activate defence mode, the tank needs to catch the impulse of hate, the desire to destroy the tank coming from a human. Conversely, in order to activate the attack mode, the tank needs to catch the impulse of fear. “The enemy controls the actions of the tank against his will” says scientist and it is a vivid statement demonstrating the interconnectedness of opponents. In the nature of any conflict lies a hidden symbiosis of opposing forces, their feeding of each other, co-dependence. Respectively, the conflict can be resolved only with the awareness of this deep connection. Tank – inorganic, dead matter, the embodiment of death, is endowed with not just human, but superhuman, telepathic qualities, thus resembling something like the Ocean from Solaris.

Neither the soldiers nor the scientist-creator can get along with this tank, since they all have some hidden motives and unresolved tensions within themselves. Only a tribe of savages and their children – the cartoon ends with a shot representing aboriginal children playing on a tank – find harmony with this machine, which is in its nature a litmus test, a mirror-image of the environment in which it appears. Let’s not focus too much on the possible colonial references of a noble savage, to which the author of the plot resorts. More important is that if the environment is permeated with conflict, the machine escalates this conflict and brings it to a discharge, to annihilation, and if the environment is calm, then the machine does not act. Just like in lots of other science fiction works (remember for example Alex Garland’s film «Annihilation»), we see a scenario of how humanity generates an entity that turns out to be a lesson for this humanity, demonstrating its weaknesses and boundaries.

Gracias por compartir este pedacito del arte de Rusia, porque cualquier arte está por encima de los conflictos políticos. Es una tristeza ver que la situación actual impulsa esta “rusofobia” absurda hacia un pueblo que no tiene la culpa de las acciones de su presidente. Pero ya está visto que en las guerras de los poderosos los únicos que salen perdiendo son los civiles.

Mi más sincera solidaridad para con el pueblo ucraniano y el pueblo ruso.